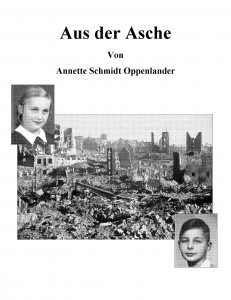

When I began interviewing my parents nearly 10 years ago, I had no idea that their tales would lead to writing a novel, the story of two children during and after WWII in a country torn apart, first by Hitler’s regime and then by every other country, Germany had tried to annihilate. Since completing the manuscript several times over, I moved on to writing novel number two while pitching number one.

I was okay with the idea not finding a willing agent to take on the complicated subject of considering a German WWII story in a context other than Nazi or Holocaust. I said to myself that I wrote to preserve the story and it was okay to stick it into a drawer and I could wait for my next manuscript to be picked up.

Then my daughter weighed in. It was not enough to write the story. It had to be read by my still living father, who, after all, is one of the two protagonists. Except for the small problem that it was written in English and my father neither spoke nor read English. He must read it before he dies, my daughter urged. But I don’t have the time, I argued. And my German is rusty. It doesn’t matter, my daughter said. It’s his story and even if it doesn’t get published, he needs to read it.

It’s no surprise for anyone multi-lingual that the speaking and writing of languages requires constant practice. As soon as one stops speaking for a while, the active memory begins to shrink. It’s like working out. The linguistic muscles shrivel just like your thighs.

I’ve been living in the U.S. since 1987 and though I have continued speaking German regularly, my written German is less than stellar. Over the years, English syntax has crept in, the use of prepositions has become less familiar and in general, my internal thesaurus is much smaller in the German language than in the English.

But dad is 82 and I was heading to see my father in May, when a few weeks before my trip I decided it was time. And so I set to work translating. The first page was torture, the second still painful but with each page, translation became easier, smoother. Thank goodness for online translation resources, my old-fashioned paper thesaurus and dictionaries.

I worked through the first 50 pages and presented them to my father upon arrival. I warned that much of my writing was imperfect, flawed with questionable grammar, definitely rougher than the English version. And that most of all, it was my interpretation of events.

He sat down within the day and began to read and wouldn’t stop until all 50 pages were finished. What had taken me weeks to do, he read in three hours.

So, I said. How did you like it?

Interesting, he said.

I waited for more, but he remained strangely quiet. Finally I couldn’t take it anymore.

What did you think? I asked.

It’s hard, he said. Difficult to read as I am diving into memories that were long buried.

I thought I’d made up most of the situations, dialogue, etc. but here was my father, telling me, that it was coming back and that it seemed real.

I only imagined how my father must’ve felt, when his father, then his brother (17) were drafted. How he, compelled by hunger, slaughtered a horse with a hammer and dragged carts of quivering meat to his mother. I only imagined how he felt when he was drafted at 16 and, with his friend, hid in the woods until the end of the war. Only to find out that all his classmates had disappeared. He had told me facts. But I filled in the feelings. Was it too much? Was I tearing open his heart with a pickaxe?

Remember, Vater, I made up a lot of it, I offered.

He nodded.

Had I expected accolades or praise? That he would be happy and laughing. I don’t know. I had tried to do the right thing and write his story. But was it the right thing? Or was it cruel to take him back to what must have been the worst time of his life, a time of horrific danger, bombs, unending hunger and emotional hardship?

How long is it? he finally said.

More than 400 pages.

I see. Will I get to read the rest?

His curiosity about what I had done with his life and heart on paper seemed stronger than the pain of revisiting his past. I will finish translation, one word, one sentence and one page at a time. However long it takes, but quickly. For my dad. Because he deserves it.

Yes, I said, you’ll get to read it all.